By Miranda Miller

Last year I joined the Authors’ Club, which organises interesting literary events in the glamorous National Liberal Club, built by Alfred Waterhouse, the architect of the Natural History Museum. It’s a short walk from Embankment Station, a monument to the prosperity and confidence of the Liberal Party (and authors) in the late nineteenth century. On April 17 I enjoyed lunch with about forty other people in the magnificent dining room.

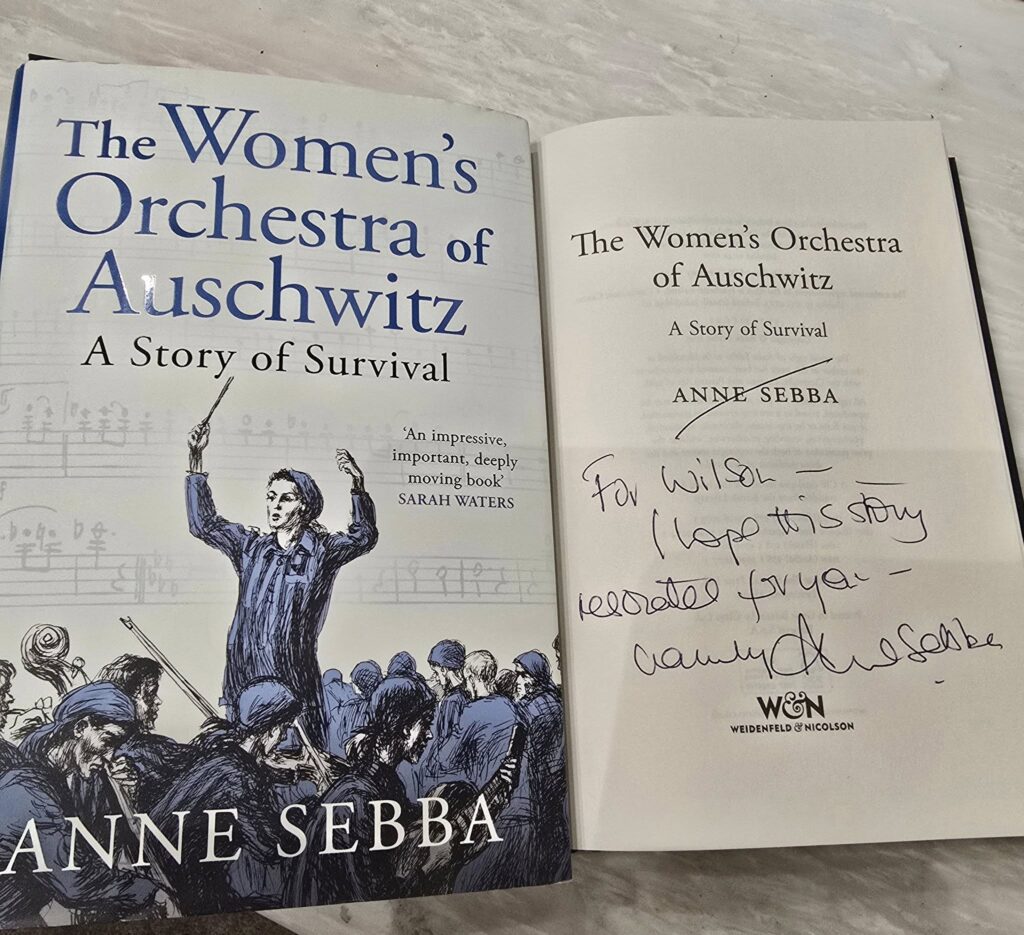

After lunch, our guest speaker this month was Anne Sebba, the distinguished historian and biographer who has written successful books about Enid Bagnold, Laura Ashley, Jennie Churchill and Ethel Rosenberg which have been translated into many languages. Her new book is called The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz, A Story of Survival. Anne Sebba began by saying that one of the reasons she wrote this book was because she didn’t think she could expect to be taken seriously as a 20th century historian unless she addressed the holocaust as a subject. In her four years of research, one of the sources she found most valuable was the Shoah Foundation, a charity set up by Steven Spielberg at the University of Southern California with some of the money he made out of his film Schindler’s List.

After lunch, our guest speaker this month was Anne Sebba, the distinguished historian and biographer who has written successful books about Enid Bagnold, Laura Ashley, Jennie Churchill and Ethel Rosenberg which have been translated into many languages. Her new book is called The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz, A Story of Survival. Anne Sebba began by saying that one of the reasons she wrote this book was because she didn’t think she could expect to be taken seriously as a 20th century historian unless she addressed the holocaust as a subject. In her four years of research, one of the sources she found most valuable was the Shoah Foundation, a charity set up by Steven Spielberg at the University of Southern California with some of the money he made out of his film Schindler’s List.

She spoke with great eloquence and accompanied her words with slides showing the faces of some of the women. As she said, one of her aims was to restore the humanity and individuality of these women, and the photos she showed us were very moving. There were fifteen male orchestras in Auschwitz (which, she reminded us, covered a vast area) but there was only one orchestra made up of women. The Nazis used music as a form of propaganda; the job of the musicians was to play jolly marching music to encourage the gangs of slave labourers in the camp to perform their macabre work.

There were fifteen women in this marching band, aged between fifteen and fifty-six. They came from a wide variety of backgrounds, not all of them were Jewish and some of them had been in the French, Polish or Dutch resistance. Alma Rosé, who was Gustav Mahler’s niece, was the conductor who “held the orchestra together” with harsh discipline, often reminding the other musicians that if they left the orchestra they would “go to the gas.” In fact, most of the women in the marching band did survive. After showing us slides of Alma and some of the other women Anne Sebba played an intensely moving few minutes of film showing one of the survivors playing Handel in 1948.

The last of these women who is still alive is the cellist Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, who came to England after the war and is now 99. In a recent. speech at the German Bundestag Parliament she said:“I swore that I would never set foot on German soil again. I was consumed by a boundless hatred of anything German. As you see, I broke my oath – many, many years ago – and I have no regrets. It’s quite simple: hate is poison and ultimately, you poison yourself.”

The last of these women who is still alive is the cellist Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, who came to England after the war and is now 99. In a recent. speech at the German Bundestag Parliament she said:“I swore that I would never set foot on German soil again. I was consumed by a boundless hatred of anything German. As you see, I broke my oath – many, many years ago – and I have no regrets. It’s quite simple: hate is poison and ultimately, you poison yourself.”

This was a very interesting and impressive event and I’m looking forward to reading Anne Sebba’s book.