By Suzy Feay

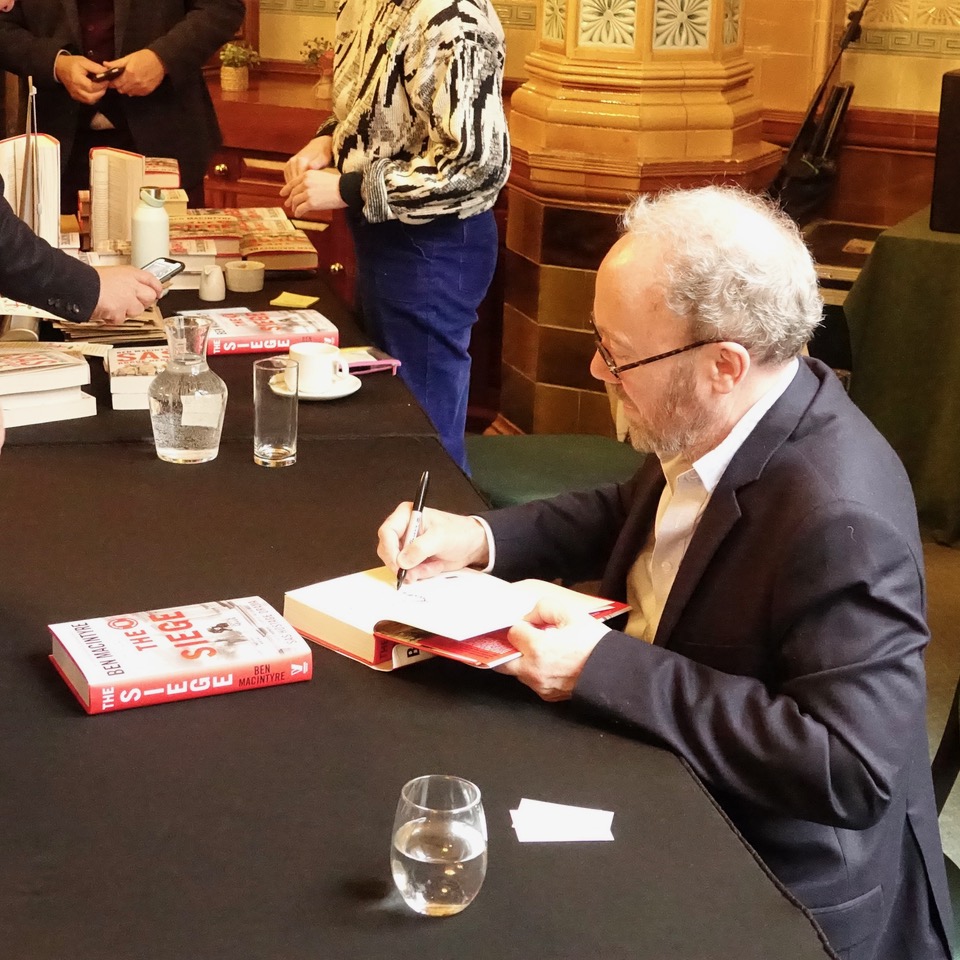

The David Lloyd George Room was packed on Thursday 16 January for Ben Macintyre’s lunchtime talk about his latest book, ‘The Siege’, the inside story of the assault on the Iranian Embassy in London that took place in May 1980. After days of tense negotiation with the Arab hostage-takers, an SAS unit stormed the building in full view of TV cameras, making them an overnight sensation and giving a boost to the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher. The turn-out at the NLC included at least one ex-SAS member, all the way from Ottawa, and proudly wearing the regimental tie.

Macintyre set out the backdrop to the drama with the aims of the six hostage-takers, who came from a brutally oppressed minority in Iran. The group had trained in Baghdad with the encouragement of Saddam Hussein, and London, with its unarmed bobbies, was assumed to be a soft target. The idea was to take Iranian hostages, arrange a speedy swap for prisoners in Iran, and release statements setting out their political goals, before being allowed to leave peacefully. But they hadn’t reckoned with the steely resolve of Thatcher.

PC Trevor Lock, the hapless bobby on the steps of 16 Princes Gate, was by his own admission, more ‘Dixon of Dock Green’ than ‘The Sweeney’. Overpowered by the gunmen, he nevertheless crucially managed to conceal his own .38 Smith and Wesson – as Macintyre pointed out, Chekhov’s famous dictum about introducing a gun into a narrative holds true here. Macintyre, who interviewed Lock and others involved, delved into the psychological aspects of the siege, which featured not just the Stockholm syndrome, but the less familiar ‘Lima syndrome’ where the terrorists develop empathy for their captives. One of the hostages, journalist Mustapha Karkouti, spoke the three languages crucial to the negotiations and stepped in to interpret, leading to unfounded suspicions that he was involved with the terrorists.

Macintyre outlined the extraordinary efforts made to cover the noise of drilling from next door, as operatives attempted to listen in by inserting microphones in the walls. As well as suspense, the talk featured welcome notes of humour – PC Lock had a fund of dirty jokes which he related to keep fellow hostages’ spirits up, all dutifully noted down by the hidden listeners. One unlucky hostage had only popped into the Embassy for a short visit and seemed not to understand quite what was going on, and kept asking if he could go now.

It was a thrilling and informative talk, leaving out details of the 11-minute mayhem of the SAS operation itself (all covered in the book). During audience questions Macintyre was asked if he would next turn his skills as a writer on espionage to operations in Northern Ireland, but that was, he conceded, currently too controversial a topic ‘even for me’.