By Suzi Feay

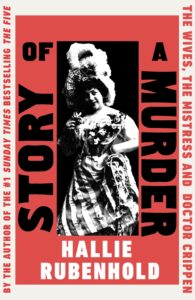

Social historian Hallie Rubenhold has followed up her pioneering account of Jack the Ripper’s victims, ‘The Five’, with an in depth new look at the case of gambler, fraudster and wife-murderer Dr Crippen. Rubenhold centres female victims rather than male perpetrators in her true-crime narratives, and ‘Story of a Murder’ is no exception. Calling her investigation ‘a natural progression of the Ripper case’, she explained how music hall artiste Belle Crippen has often in effect been blamed for her own murder at the hands of her manipulative husband.

Social historian Hallie Rubenhold has followed up her pioneering account of Jack the Ripper’s victims, ‘The Five’, with an in depth new look at the case of gambler, fraudster and wife-murderer Dr Crippen. Rubenhold centres female victims rather than male perpetrators in her true-crime narratives, and ‘Story of a Murder’ is no exception. Calling her investigation ‘a natural progression of the Ripper case’, she explained how music hall artiste Belle Crippen has often in effect been blamed for her own murder at the hands of her manipulative husband.

But had he already killed? ‘Crippen’s first wife Charlotte always slips through the net,’ Rubenhold observed. From an impoverished Irish background, she died young in mysterious circumstances. Was she the first victim?

Rubenhold spent the two Covid years reading the British newspaper archive online to research the case. Her method always involves listening to witnesses who have been ‘pushed to the side’. The truth is ‘never just a singular voice’. She pointed out that if something dramatic occurred over the course of this well-attended lunch, every person present would give a slightly different account. (Fortunately, nothing did.)

The lighter side of the investigation involved looking into the Music Hall Ladies Guild; Belle was its treasurer. Rubenhold presented a rounded picture of the well-travelled and resourceful Belle Crippen, far from the caricature that’s been drawn before: ‘a joke figure, a shrew, unfaithful… there’s no evidence of this.’ The other fascinating element of the story is Dr Crippen’s lover, ‘lady typist’ Ethel Le Neve, who started calling herself Mrs Crippen soon after Belle vanished. The ladies of the Guild became suspicious when Le Neve was spotted wearing Belle’s diamond brooch.

The 1910 case captured the public imagination because it was the first ‘real-time crime investigation’, with newspaper readers avidly following the high-speed chase across the Atlantic as detectives pursued the fugitive duo. Crippen was executed; Le Neve, who was acquitted, died as recently as 1967, understandably keeping the secret of her notoreity to the last.

Asked how it feels to delve into the horrific details of the crimes she writes about, Rubenhold explained that after the initial shock, her approach becomes more clinical: ‘you have to look at it in a scientific way.’ The talk gave members a fascinating glimpse into a murky case that has never lost its grim fascination.