Martin Amis was a one-man multiverse. A cool, sulkily unsmiling, hilariously ironical, perma-smoking, laser-brained novelist, critic, essayist, media pundit and reliable controversialist, he took the English language to new levels of baroque extravagance. He turned sentences that Evelyn Waugh might have envied, and spun paragraphs of molten disgust that would have impressed Rabelais.

He was the flag-bearer and star of a generation of modern writers who flourished in the 1980s, but was also their John the Baptist. When his first novel The Rachel Papers was published in 1973, his was a voice crying in the wilderness for more wit, more ruthlessness of description, more sexual licence. The Big Beasts of fiction that surrounded him were becoming atrophied – Graham Greene, Iris Murdoch, William Golding, Angus Wilson, John Fowles – and the comic novel languished in the hands of his father and the university drolls, Malcolm Bradbury and David Lodge. Amis Jr seized the moment with glee. The first page of Rachel finds Charles Highway describing how he possesses “one of those fashionable reedy voices, the ones with the habitual ironic twang, excellent for the promotion of oldster unease” – and oldster unease was the book’s main target, along with feminist sensitivity. Its most startling passages described Charles’s pitiless descriptions of spotty, teen-male bodies and his attraction/repulsion response to female sexuality.

Although he was seen, by some critics of his first three novels, as a sex-obsessed snake in the garden of fiction, he was also the most self-consciously literary of writers. The names (or allusions to the works) of DH Lawrence, EM Forster, Ernest Hemingway, Henry Fielding, Sigmund Freud, Oscar Wilde, Philip Larkin, Gerald Manley Hopkins, AE Housman and William Shakespeare are all dropped in the first thirty pages of The Rachel Papers. By page 60, Dickens, Dylan Thomas, William Blake, Jane Austen, George Herbert and Franz Kafka had also been press-ganged into the action. And even as new readers recoiled wide-eyed from the death-haunted grotesquery of his next fictions, Dead Babies (1975) and Success (1978), Amis was emerging, in the review pages of the British press, as a ferocious upholder of literary rigour, narrative energy and comic attack. When his writings from 1971 to 2000 were collected in The War Against Cliché (2001), his critical voice over 500 pages of analysis was revealed as a thing of wonder: beadily attentive to language, pungent, fanged, subversive and pitiless in laying waste to whole careers and reputations.

His later books dealt with weightier themes of humanity’s folly, imbecility and willed self-destruction. Reading the progress of the monstrous Anglo-American John Self in New York as he negotiates insane amounts of drink, drugs, expensive handjobs and meetings with attitudinous film stars (it was based on his experience of scripting the film Saturn 3, starring Kirk Douglas) is a comic romp that gradually shades into disgust at the hectic consumerism, and the social degradation of the pornified modern world.

Amis’s horrified fascination with the concept of entropy – the tendency of everything to proceed towards destruction – animated later works, most notably Einstein’s Monsters (about the nuclear threat) and London Fields, despite the galloping implausibility of its plot: just being in the company of the Amis narrating voice, hearing its emphatic, propulsive, take-no-prisoners delivery carried you through some minefields of potential disbelief.

I was fortunate enough to meet Martin Amis on several occasions. At lunches he was terrific company, generous in conversation, shamelessly gossipy and particularly keen to pass on stories about his father Kingsley, whom he revered.

I interviewed him in 1981 about his fourth novel Other People: A Mystery Story and remember the absolute delight he showed at the prospect of visiting his hero Saul Bellow at his home in Chicago in a year’s time. In 1989, we had lunch at London’s Waldorf Hotel around the publication of Einstein’s Monsters, during which I pointed out that much of the emotion in the stories was centred on families, fathers and children, and the vulnerability of the young and weak. Had this anything to do with Amis’s own status as the father of Louis (then two) and Jacob (six months)? “Becoming a father,” he’d replied, “repaired my damaged sense of time. I had ceased to care, in a sense, about the future. I was passive about it. Children represent your attachment to the future and remind you that you’re attached to the past as well.”

I admitted to having an unashamed fan-boy moment as I watched Amis, across the dining-table, devour a plate of moules marinieres, deftly extracting the orange mussels from their shiny black shells with speed and precision, like a skilled artisan. I related it to his writing – “selecting the right words from the lexicon of language, yanking them from his memory with the pincers of his creative mind, savouring them, dipping them in some marinating wine…”

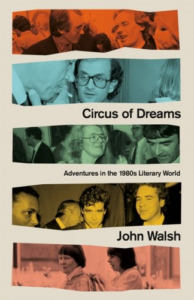

Twenty-three years after that rather breathless summation, I wrote in my book Circus of Dreams: Adventures in the 1980s Literary World (2022) about how his reputation has endured. While some of his late fictions, especially Yellow Dog (2003) and Lionel Asbo: State of England (2012) had been given a rough ride by the critics, I wrote, ‘with the publication of The Rub of Time — Essays and Reportage 1986-2016 and of Inside Story (2020), his mélange of autobiography, politics, thoughts on death and sections on How to Write, all misleadingly entitled ”a Novel”, Amis’s real achievement became clear. It’s his commitment to style rather than story, to making war on clichéd words and flabby thinking. He goes so far as to say that “Style…is morality.” His whole project has been to find a voice uniquely fitted for expressing, and challenging by wild satire, the preoccupations and grotesque obsessions of the 20th and 21st centuries, whether he’s dealing with political falsehood, moral dyslexia or global wrong-headedness.

Twenty-three years after that rather breathless summation, I wrote in my book Circus of Dreams: Adventures in the 1980s Literary World (2022) about how his reputation has endured. While some of his late fictions, especially Yellow Dog (2003) and Lionel Asbo: State of England (2012) had been given a rough ride by the critics, I wrote, ‘with the publication of The Rub of Time — Essays and Reportage 1986-2016 and of Inside Story (2020), his mélange of autobiography, politics, thoughts on death and sections on How to Write, all misleadingly entitled ”a Novel”, Amis’s real achievement became clear. It’s his commitment to style rather than story, to making war on clichéd words and flabby thinking. He goes so far as to say that “Style…is morality.” His whole project has been to find a voice uniquely fitted for expressing, and challenging by wild satire, the preoccupations and grotesque obsessions of the 20th and 21st centuries, whether he’s dealing with political falsehood, moral dyslexia or global wrong-headedness.

That voice, that style, may be too cool, too machine-tooled for some; but it seems the voice of the utmost sanity.

The former literary editor of the Sunday Times and the Independent, John Walsh is the author of the novel ‘Sunday at the Cross Bones‘ and two previous memoirs, ‘The Falling Angels’ and ‘Are You Talking to Me?: A life in the movies‘. His latest book is ‘Circus of Dreams: Adventures in the 1980s literary world‘. He chats to Suzi about meeting heroes such as Anthony Burgess, interviewing luminaries like Martin Amis, and being at the heart of literary London during a tumultuous decade.